Planting the tiny seeds of sagebrush restoration

Pitkin County’s sage growing at the Upper Colorado River Environmental Plant Center.

Can unimaginably tiny seeds help turn back the clock a century or more in the Brush Creek Valley? Pitkin County Open Space and Trails is determined to find out.

Already a year in the making, a sagebrush restoration project will hit high gear this month when seeds collected a year ago are planted in a series of test plots that have been created in the valley between Brush Creek and Brush Creek Road. Sagebrush seedlings, carefully nurtured from the some of the harvested seeds, will also be planted. In all, three seeding/planting methods, with and without irrigation, and with and without fencing, will be tested across 12 test plots.

It’s a complicated science project with a simple goal: determine the most effective method of restoring mountain big sagebrush – which can be difficult to establish – to the local landscape. Anyone who wants to watch the project unfold will have an easy vantage point. The test plots are visible from Brush Creek Road and the Brush Creek Trail.

In addition to the plantings, branches of local mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata subspecies vaseyana) that are ready to drop their seeds will be delicately harvested and transported to planting locations outside the test plots where they’ll be piled on bare ground and allowed to drop their seeds to the soil, mimicking natural sagebrush seed dispersal.

The plots were mowed and tilled last year, and ground preparation continued this year to suppress the non-native grasses and weeds that dominate this former agricultural field. Low-visibility fencing was recently installed to give some of the sagebrush a chance to grow without being devoured by grazing wildlife. White flagging on the fencing will remain through the winter to help animals see the barrier.

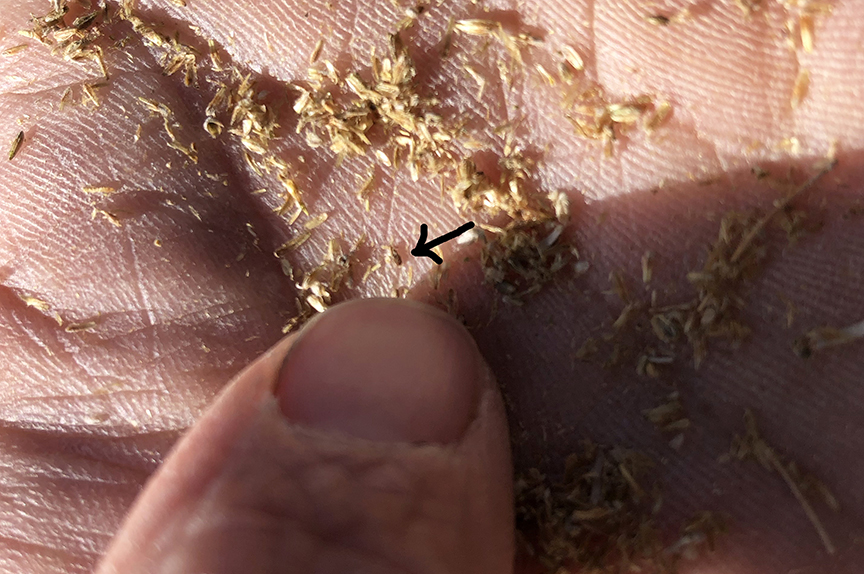

The all-important local sagebrush seed was collected in early November 2020 by a small team from the Upper Colorado River Environmental Plant Center in Meeker and a handful of OST staffers. The flowering stalks of mountain big sagebrush were cut in the Seven Star area of Sky Mountain Park, at Burlingame Open Space and Moore Open Space. Thirteen large sacks, stuffed with the stalks, were carefully winnowed back at the center, producing 2.2 pounds of seed, according to center Manager Steve Parr. That may not sound like much, but there are 1 to 1.5 million of the miniscule seeds in a pound of seed, he said.

The use of local seed is crucial to the experiment. There are many subspecies of sagebrush and even planting seed of the same subspecies, gathered elsewhere, could doom the experiment to failure, according to Parr. The young plants could die, or, on the other extreme, outcompete the native variety.

“As local as you can get is best. Close to local is next best,” he said.

Some of the Pitkin County seed was caringly cultivated in the center’s greenhouse. The seedlings were then moved to an outdoor facility to acclimate the plants to an outdoor environment in preparation for this month’s planting. There will be slightly more than 600 seedlings at the ready for the test plot experiment. The seedlings are a few inches tall, since most of the biomass so far is in the root – what Parr calls “the business end” – where sage seedlings devote most of their energy initially.

Sagebrush that grows from the seeds that will be sowed in the plots should catch up to the size of the seedlings in about 3 years, according to Parr.

In the natural environment, millions of seeds drop to the ground from a mature sagebrush if conditions are right and the plant flowers. Young specimens of big mountain sagebrush are invariably found growing near parent plants, but new plants typically take hold next to decadent, old sage. Seedlings don’t compete well with healthy sagebrush.

“In a good stand of sage, you won’t see a lot of seedlings,” Parr said.

At the test plot site, agricultural use of the land likely dates back a century or more. Non-native pasture grasses and weeds long ago supplanted what was most certainly a sagebrush shrubland before ranching began there. Restoring the pasturelands with mountain big sagebrush may take some time, as sagebrush is a slow-growing species, but it will eventually improve habitat for wildlife, including birds, and boost soil conditions.

Open Space and Trails hopes to determine a reliable method of restoring sagebrush that is not dependent on intensive applications of herbicide. Sagebrush shrublands are one of the most imperiled ecosystems in the West as a result of development, overgrazing, climate change, encroachment of pinyon and juniper, and other factors. Restoration of this habitat is an open space priority. The project is detailed as a management action in the draft 2021 Sky Mountain Park Management Plan that is currently under review (pp. 29 and 56). Ideally, the knowledge gleaned from the test plot experiment will be transplanted to other restoration efforts, locally and regionally.

In preparation for this project, OST reached out to other entities that have tried to regrow sagebrush. One of them, Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming, has had mixed success, even with the use of herbicides to eliminate smooth brome and other non-natives prior to sagebrush seeding. The park’s biologist is particularly interested in the results Pitkin County sees with its tilling regime.

It really is a field where experimentation is needed to identify methods that work locally, that are scalable and that have the greatest chances for long-term success, said Liza Mitchell, OST natural resource planner and ecologist.

– By Pitkin County Open Space and Trails

- Flowering sagebrush

- One tiny seed

Test plots in the Brush Creek Valley